Battery Point

Sun Jan 05

Tasmania's laughable defence come heritage icon

Written by: Josh Withers

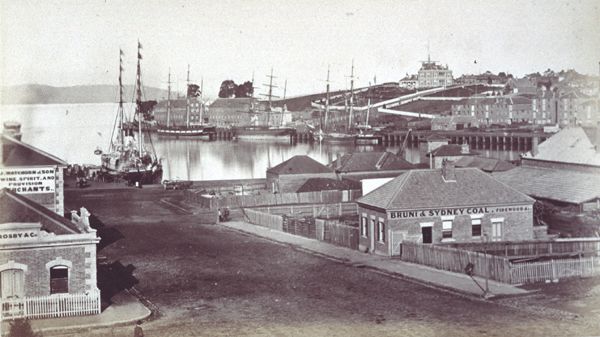

Battery Point, nestled along the southern shore of Sullivan’s Cove, was chosen for its strategic location to protect the early settlement.

It was on this point slightly west of Sullivans Cove in 1818 that Lieutenant-Governor David Collins established the first battery of guns to defend Hobart Town and named it such.

The colony at Van Diemen’s Land was considered a weak spot in the broader British Empire’s defensive strategy, exposed to potential threats from rival nations such as America and Russia, despite being “too far south for spices” it was a hotspot on the roaring forties and rather isolated from the burgeoning number of other English colonies.

During the early 19th century, fears of attack from Americans (still viewed with suspicion post the War of 1812) and Russians during periods of heightened European conflict were very real.

Hobart’s vulnerability as a distant outpost with sparse resources and limited military infrastructure meant its defences, including Battery Point’s guns, were largely symbolic rather than genuinely effective. The sense of fragility shaped much of Hobart’s early planning and development.

Cottage Green

As the first residence outside the original “camp” of Hobart Town, Cottage Green was 30 acres west of Salamanca and built on in 1805 by Reverend Robert Knopwood. It soon became home to the batterys thatgave the point its name.

The Prince of Wales Battery, established in 1818, was meant to provide a first line of defence against seaborne threats. However, like much of the colony’s military infrastructure, it was under-resourced, poorly built, with few artillery pieces and limited personnel trained to operate them.

The guns served more as a deterrent than a serious defensive measure with volunteers hoping enemey ships would be merely deterred and hopefully not have to be shot at.

A signal station and guard house were built in 1818 on Battery Point. These installations allowed the settlement to monitor ship movements and send warnings.

By the 1850s, the Crimean War (1853–1856) reignited fears of Russian aggression and Hobart, as a remote colonial outpost, seemed particularly vulnerable to the people back in London. Efforts were made to modernise the Albert Battery during this time, but these were largely reactive and insufficient to meet the evolving threats of the era.

Despite its defensive challenges, Battery Point became a thriving community. Wealthy shipowners, merchants, and officers built homes along Salamanca Place and Hampden Road and the lanes in between including Arthur’s Circus, while shipbuilders, dockworkers, and sailors lived in modest cottages nearby.

Arthur’s Circus

Arthur’s Circus, a circle of Georgian cottages originally built by Governor George Arthur for retirees and garrison officers, reflects Battery Point’s military roots.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Battery Point became the site of a different kind of battle: the fight between developers and heritage advocates. While developers pushed for modernisation, heritage lovers argued for the preservation of Battery Point’s unique history.

After a bitter council struggle, the convict-era-celebrators prevailed, ensuring the area’s survival as a window into Hobart’s colonial past that we can gladly show to visitors.

The resulting paperwork - the Battery Point Planning Scheme - leaves the point as the only suburb to have one all to itself which is nice.

Glass-shatteringly-loud

When the Hobart Town Volunteer Artillery practised firing the guns at the Albert Battery, the booming sounds echoed through the settlement, shattering windows and unnerving residents. The practice highlighted the colony’s lack of preparedness and the crude nature of its defensive infrastructure. Later they would visit the local homes asking them to open the windows prior to practice.

Kellys Steps

A set of stairs from Salamanca Place to Battery Point named “Kelly’s Steps” are seemingly on every tourism brochure - because they’re convict built, old, and there’s a plaque at the top seeemingly because the steps were improved six years after they were built - built to bridge Salamnca to the first Australian-born-European master mariner and pilot’s new estate above Salamnca Place in 1834. James Kelly was born in 1791 at Parramatta, New South Wales, three years after the New South Wales colony was established.

Max Angus recalls of his Battery Point childhood in the 1920s:

“the smell of raspberry jam at the Jam Factory was wonderful. The factory was slap against Kelly Steps on Salamanca Place. Further on, at the wharves opposite Parliament House, you got fishing smells, and the spicy aroma of fresh timber. The salty, fishy smells of the waterfront and the slightly rancid pong of fishing boats at anchor have survived the area’s gentrification, still evoking the romance of the sea.”

The Oomph! Coffee roasting scandal

The more recent story that confuses Hoabrtians of Battery Point is one where the residents of Battery Point became confused between their nose and their addictions.

In 2006 Carlos and Nikki Kindred of Oomph! Tasmanian Gourmet Coffee had to fight for the right to roast their own coffee beans in Battery Point.

Roasting coffee had been labelled as “light industrial” and therefore should move out of Battery Point.

The roasters went to battle and won, but eventually left the suburb, and still today Battery Point is left without good coffee.